UNITED STATES—Astonishing how things blossomed after joining the Spanish-language theater group. After one of the group’s rehearsals Rafael, the director, invited me to check out a new cultural group. He gave me a street number on Vermont Avenue that I scribbled on a scrap of paper. They were meeting the next Saturday afternoon. Bring something to read, Rafael said.

I walked from Estrella Avenue to Vermont, nervous and apprehensive. Going to a strange place, reading in public, my gringo accent. When I reached Vermont, the street numbers took a suddenly familiar turn. There it was: north of Jack in the Box and south of the 10 freeway. The meeting place was up a musty flight of stairs through a doorway located next to the Librería Azteca. Upstairs was a spacious meeting room with white walls and a wooden floor painted gray.

People were trickling in from the back door, which was the usual entrance. Here one Saturday every month people from pretty much all Latin-American countries met: Peru, Honduras, El Salvador, Argentina, Mexico and Colombia. Here they shared their creativity in words and song and story. And there would soon be among them a kid from California, the lost province of the Spanish empire.

Gosh, I was nervous. It seemed like I hadn’t spoken in public since my 8th grade graduation. Then to my surprise—there stood Antonio Ayala, the owner of the book store, and a teacher in books and life. By the strangest route I had come full circle to this homecoming in the meeting room of the Mason’s Lodge above the print shop and the dress shop and book store.

Others sang, shared stories and declaimed poetry like a man from New Mexico who was a civil engineer, but when it came to poetry he would pull out the Latin American art of performing melodramatic verse, often about the orphan, the grieving mother, the drunken father, the cruel rich. I had brought something to read from my first book.

So far everyone in that room had been respectful, sincere in their enjoyment and reactions. And everyone had had a place in front for a few undivided moments. But that didn’t placate my nerves. Now my shoulder was being tapped—it was my turn—and my butt was being launched to speak in public. Piece of cake. All I had to do was endure the nerves and manage not to melt like a pillar of salt rained on.

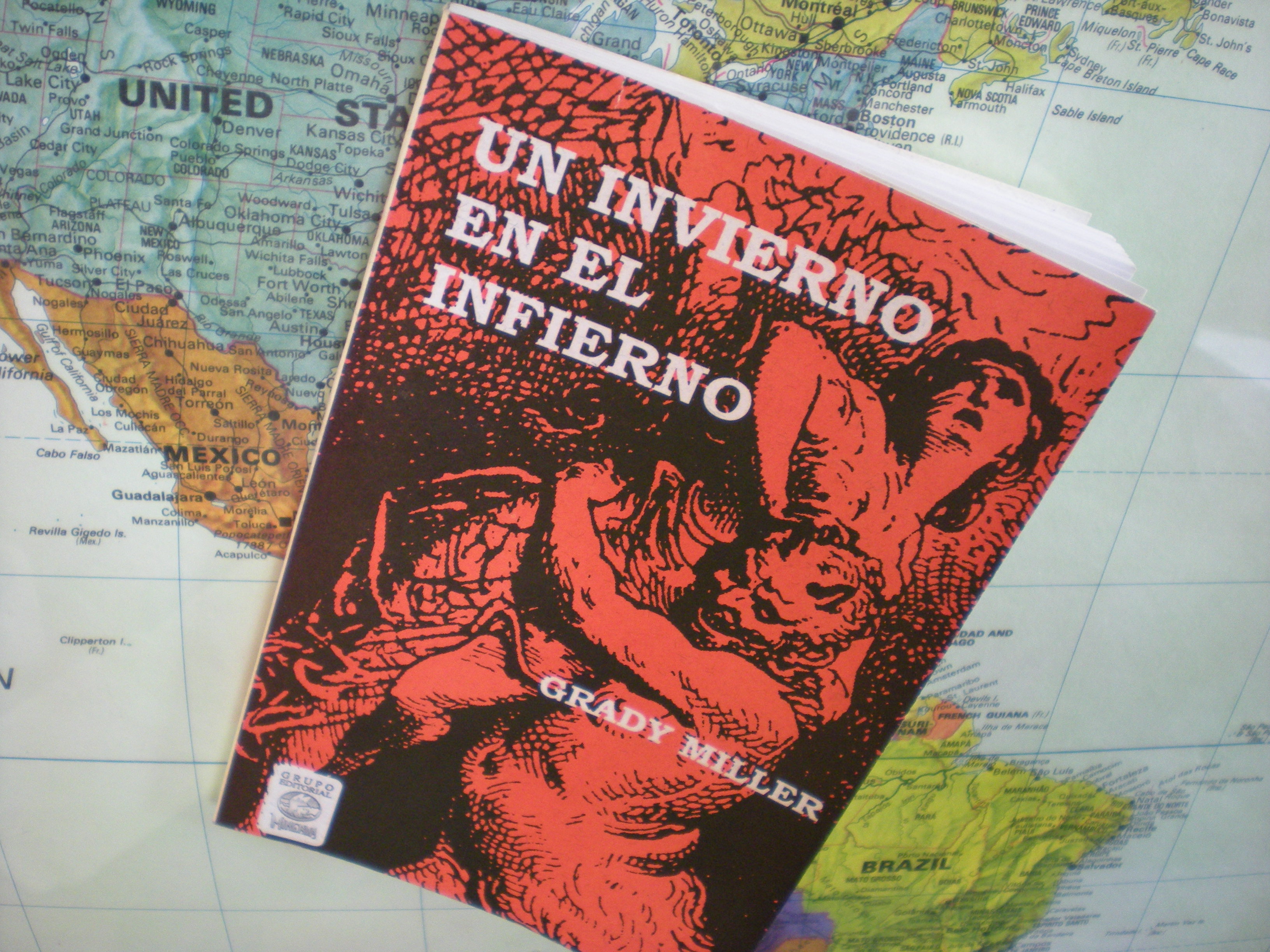

Don Antonio introduced me to the group, “There’s this young gringo who came into my shop one day. He went to live for a year in Mexico. For some reason he likes Spanish, and he wrote a book that was published in Mexico.” My nose buried in the book, hands trembling, I read the passage about the raindrops in “A Winter in Hell:”

I gaze at the movement (fascinating as fire) of rain on a window. From the top of the window a single drop slides down the glass toward the bottom, detouring between archipelagos of water, flowing, offering itself, sharing its own molecules, taking on new ones, still unimpeded. Although the first waters scarcely reach the bottom intact, the individual drop still exists.

With Geiger counter ticks, rain strikes the window, full of drops of time, other lives, pouring into the ocean of lost time.

There was applause and appreciative smiles: these were the first precious drops felt by parched earth after a long drought. The second Saturday of every month was to become a much-anticipated and cherished event. I survived my first participation and Bohemia de Los Angeles, and it would be marked on my calendar ever after.

Going there, presenting something new every month—these awoke a long forgotten feeling of something that had stopped a long time ago—the feeling of going to church, because that’s where I first made people laugh in public. The big meeting room with the wooden floors painted gray was now my church.

Humorist Grady Miller is author of the humor collection, “Late Bloomer,” available on Amazon. Grady can be reached at grady.miller@canyon-news.com.