SAN FRANCISCO—On October 24 the Azerbaijani community held a rally, titled “Recognizing the Refugees and Victims of Nagorno Karabakh Conflict,” in the San Francisco Embarcadero plaza with the stated purpose of raising awareness about the victims of the current conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh as well as surrounding regions.

Individual community organizers said the purpose particularly was to raise awareness about the 700,000 to 1 million Azerbaijani made refugees during the war fought between the two former Soviet republics, Armenia and Azerbaijan, between 1991 and 1994.

This was seen as an issue that Azeri community activist Yasmin Bashirova said “never gets mentioned in the media.” The event presented survivors of the war who fled and have not been able to return to their homes for nearly 30 years.

The first speaker, Ayka Agayeva opened up the rally by mentioning the UN “calling for the complete withdrawal of Armenian occupying forces from the territory of Azerbaijan.”

She went on and said that Armenian forces “occupied 20% Azerbaijani territory, forcing 700,000 Azerbaijanis to leave their homes.”

One protester held up a sign made in a print shop that read: “FACT: Armenia occupied 20% of Azerbaijan.” Others carried signs about coexistence. Some had more assertive tones, with signs with protest slogans such as “Stop Armenian Aggression,” “Stop Armenian Terrorism,” and “Don’t believe Armenia.”

Similar to the Armenian demonstrators who gathered at the Golden Gate Bridge on October 10, Azerbaijani protesters also had protest slogans slandering the adversary with references to the Nazis. One man held up a sign that read: “ARMENIA GLORIFIES ITS NAZI COLLABORATORS.”

Azeri protesters carried signs with the slogan “Karabakh is Azerbaijan.” However, those on the Armenian side of the conflict carried signs with the slogan “Artsakh is Armenia.”

The rally included a series of narratives from survivors of the war, particularly those of the Khojaly Massacre in which some 600 civilians were killed. The first speaker said that women and children were massacred “without mercy and without remorse.”

Before turning the microphone over to survivors of the Khojaly Massacre, Agayeva said:

“The human cost of this occupation has been staggering. Those that did survive the attacks have been traumatized for life and generations of childhood have been lost forever. One of the biggest atrocities committed during that period was in Khojaly, which Human Rights Watch described as unconjurable acts of violence against a civilian population. Six hundred women, children, and elderly were massacred as they tried to flee their homes when the Armenian forces were advancing on their town. I watched these images as a child. I watched these images I could not forget.”

Anar Usubov, a business owner and former Azerbaijani refugee who survived the Khojaly Massacre, shared about his experience fleeing the town, which he says was occupied in a “cruel way.”

“I was an 11 year old boy when the Khojaly massacre happened and I will not even wish my enemies what happened to me.”

Khojaly was besieged and all roads leading to the city were blocked. “There was no gas, electricity or other facilities in our city,” Usubov said. “All work places, shops, and schools were closed.” He said the siege began in December 1991.

The massacre began during the night of February 25, 1992, when tanks arrived: “Only when tanks came into Khojaly people understood it was serious. Me and my family fled with some relatives and neighbors to the forest to reach the closest Azerbaijani settlement, which was 15 kilometers away.”

Usubov said the citizens who fled to the woods were captured and tortured before they were released in return for money or petrol. He described his group of some 45 people being pursued by Armenian soldiers:

“It was winter and I remember it was very cold and freezing. We were in a group of around 45 people. Suddenly we were surrounded by Armenian soldiers. Later we understood they had been following us the whole way. They started to shoot at us and we shot back, but among us there were a lot of kids, women and elders, so we decided to stop shooting and surrender.”

Usubov and other survivors of the Khojaly massacre were then taken as hostages in the town of Askeran. “We were brought with around 60 other people to the jail, a dark and cold building.”

Life in the camp was “terrible” and “horrifying.” Conditions included dirty water and rotten food: “We got dirty water once a day. The water was being given in a dusty basket. We got rotten potatoes and peelings of rotten potatoes to eat. Often we melt frozen snow to drink.”

The survivor of the ordeal said that “every second or every moment could be the last moment of your life.” He described the torture the hostages experienced as “very cruel.”

“Armenian soldiers pulled out the golden teeth of all hostages. They were burning hands and fingers of young male hostages, putting and smashing their fingers and nails between doors. Girls and women were insulted and raped over and over again.”

Many of the wounded hostages were in a critical condition. Usubov said that hostages received no medical treatment whatsoever. “Body parts of many hostages froze, especially toes and fingers had to be amputated after the captivity.”

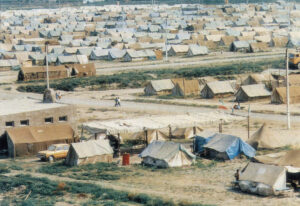

After being released, Usubov and his cohort went to Aghdam, where his relatives lived. In 1995, Aghdam got occupied by the Armenian forces, forcing him to flee again. “Then we had to move to Naftalan and Barda where we lived in refugee camps, which were organized by International Humanitarian organizations and UN humanitarian aid.”

Life in the refugee camps was in his own words, “indescribably poor.” Basic life could not be sustained because of horrendous conditions and refugee camps were dependent on international aid.

“We lived in squalor without electricity, gas or water, and there was no work.” The refugee population was plagued by a lack of vegetables, nutritious food, and medicine. Basic life could not be sustained and refugee camps were dependent on international aid. Refugees died from tuberculosis and malaria.

(Courtesy of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Flickr Page)

Usubov lived in this way for three years before getting a house with his parents: “We lived like this for three years. After that we got a house in Barda, where my parents still live till today. After the tragedy we never saw our homes again and we lost all our property.”

“After 26 years passed by there are still one million internationally displaced persons from Nagorno-Karabakh waiting for the return to their homelands,” he concluded.

Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev has demanded that Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding regions under the administration of the self-declared Republic of Artsakh be returned to Azerbaijani control. Armenians view Nagorno-Karabakh as a historically significant part of the Armenian homeland and refuse to withdraw.

Rally speakers called for coexistence and a return of refugees to territories deemed under Armenian occupation by international law. Armenian withdrawal from internationally-recognized Azerbaijani territory is seen as a primary goal in the peace process.

Zarifa Musayeva, a social worker whose ancestors are “originally from Karabakh,” said that Armenians and Azeris lived together as neighbors and friends for several centuries:

“My grandfather from Shusha, grandmother from Kalbadjar and my father was born in Agdam. When Armenians claim territory of Nagorno Karabakh they completely ignore the fact that we also lived in those territories and it was our land for thousands of years. We lived together with Armenians for centuries and never had any serious issues. I had Armenian classmates, neighbors and co-workers while I lived in Baku.”

He said the current conflict is as a result of the military occupation by the Republic of Armenia as well as military activity by separatists in the self-declared Republic of Artsakh.

“However, starting early 90s Armenians started to claim the ownership of Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenian forces with help of Armenian forces took control of Karabakh and seven adjacent districts.”

What Armenians view as a recapture of territory is from the Azeri perspective, an occupation that resulted in a refugee crisis. “Many relatives and friends became internally displaced persons in their own country.”

(Courtesy of BBC 2’s “Places That Don’t Exist” show)

Yasmin Bashirova, a community activist and Stanford graduate with an MS in Energy Resources Engineering played a leading role in the rally. “Our community wants nothing but peace and co-existence between the two nations, but we must balance the territorial integrity and national security in this issue,” she said.

Bashirova said one of the “key” topics the Azeri demonstrators were trying to get across was UN resolutions regarding the disputed or occupied territories:

“One of the key topics that we are trying to get across is that the UN security council passed four resolutions demanding immediate withdrawal of the Armenian forces from Azerbaijani territories.”

Aygun Suleymanova, Senior Director and Head of AI Product Marketing at Salesforce and social media admin of the Azerbaijani Cultural Society of America, expressed frustration at international sympathy for the Armenian side of the conflict. He said that Armenia is the occupying force, but expressed desire for reconciliation and coexistence.

“Many years ago I visited one of these refugee camps in Azerbaijan. Despite the trauma, despair, confusion as to why world leaders are siding with occupiers, these refugees did not let hate define them. Just like the rest of us, they spoke of co-existence and peace not revenge, with the burning desire to return to their ancestral homes.”

Suleymanova concluded with a message of hope for peace with Armenians in the future. “And that is the hope with which we live today because we know (and we have seen) what the peaceful co-existing future can look like for our nations.”